Note: Except where noted, this history sources from The Rise and Progress of Shiloh Baptist Church, written by Franklin A. Guinn in 1905.

If you stand at the corner of Clifton and South Streets today, you might not realize you're standing on what was once the edge of the city.

In 1845, Clifton and South was where a young boy named Franklin Guinn helped his church family build a church from scratch. Brother Sheppard Patterson donated 500 bricks. The women scrubbed. The men laid bricks. And the kids—kids like Franklin—hauled out the trash.

He was seven.

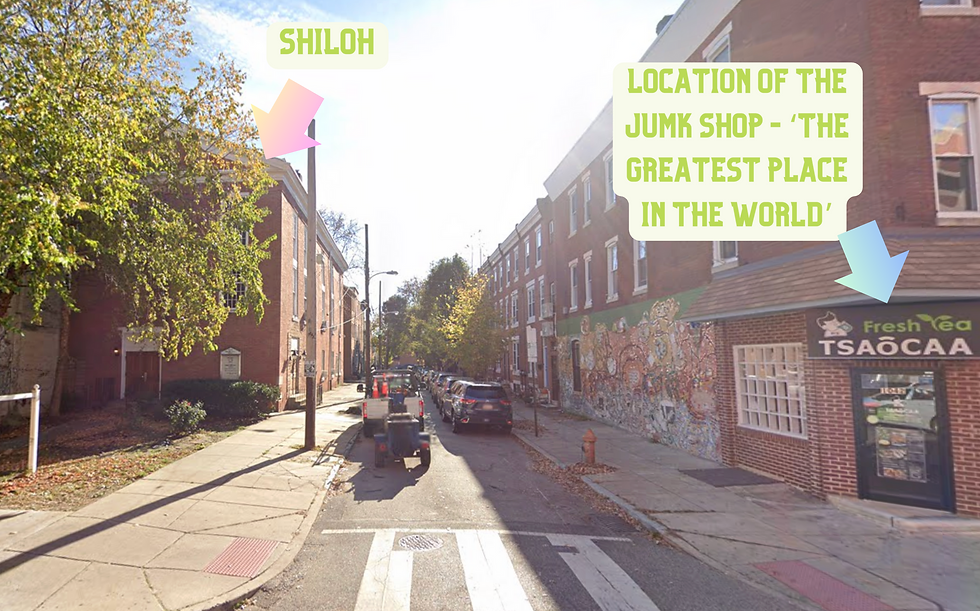

Here is Shiloh today. The building still stands and is now an AME church.

In his 70s Franklin Guinn wrote The Rise and Progress of Shiloh Baptist Church.. And it was during a read of this book that all of these incredible stories popped out (Peekaboo!) and I am staying up late to make sure that I pass on that wonder to you!

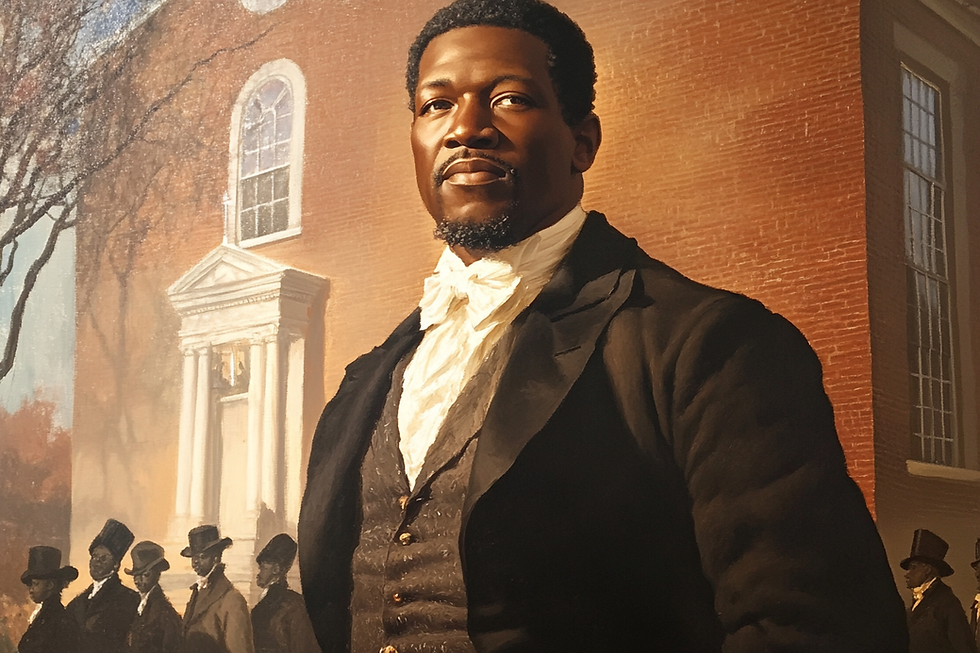

Growing up In Shiloh Baptist Circa 1845

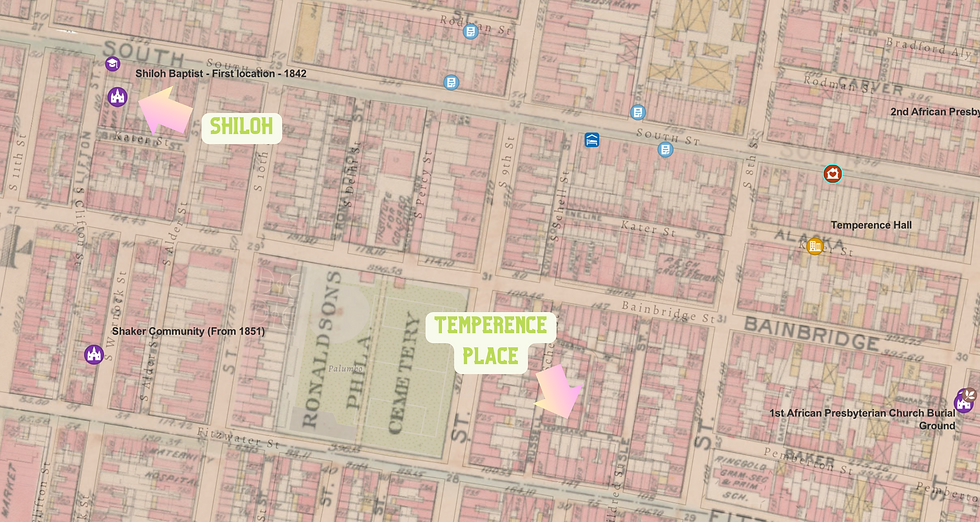

In the beginning, Shiloh was just a small off-shoot congregation of First African Baptist. Starting around 1842 the congregation rented a wooden building in the backyard of the house owned by Absalom Jones at 409 South 11th Street, where the Banneker Institute and the African Lodge met.

That’s where Shiloh started. Franklin’s father Peter was there from the beginning. And even when the church didn’t have a pastor, Reverend Jeremiah Durham—who lived just around the corner on Barley Street—would step in to preach.

Franklin remembered his mother singing “Roll On Silver Moon” during one of those early programs. She played guitar.

He also remembered being scared of the church ladies, especially Aunt Jane Brooker. And "Bud Jack" terrified him 😂.

As Shiloh grew on Clifton, Franklin must have spent a lot of time in the neighborhood. He talks about the geese, chickens and pigs that roamed Clifton and Kater. And he also fondly recalls the ‘greatest place on earth’, an old junk shop at the corner of Clifton and South.

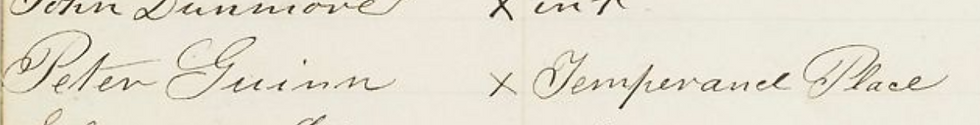

We know from the 1847 Census that he grew up on Temperance Street—what we now call Pemberton—just above Fitzwater Street.

Here's the locations as shown on our map with the 1895 street overlay.

Back in 2018, I took pictures of this block, because it is now decorated with gorgeous murals. Maybe some of Franklin’s artistic energy lingered from the 1840s and into the present, whispering in the ear of the 21st century artist to build life into the walls here.

Two people in the household had been enslaved and had purchased their own freedom for $150. Most likely those two people were his parents.

The census indicates that the children were in school at the Lombard street school, at 6th and Lombard. Franklin probably was in class with Octavius Catto and Jacob C. White Jr., who were also at the school at the time.

And then....Music!

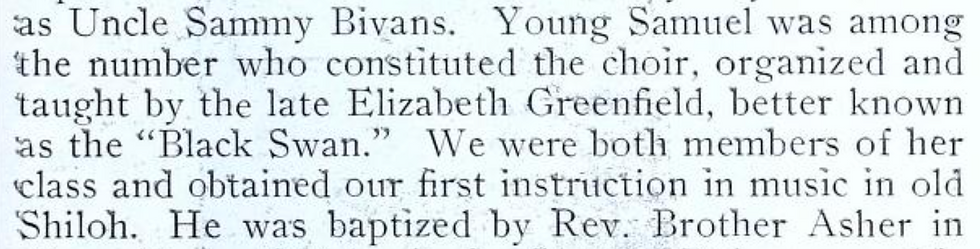

And then something unexpected happened. Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield—the Black Swan—came to Shiloh. She began teaching music. Not just solos, not just hymns. She was building something.

Franklin was one of her students.

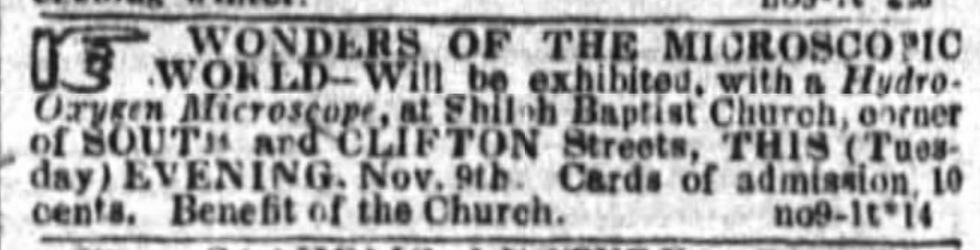

By the time Franklin was 14, he was probably in the audience when Shiloh hosted a public science lecture in 1852.

Advertised as ‘Wonders of the Microscopic World’, an ‘Oxygen Microscope’ was exhibited to the community with all proceeds benefiting the church.

Shiloh must have been a progressive place. We know that in 1855, Black women from Shiloh led the organizing committee to support Mary Ann Shad Cary in her famous 1855 whirlwind through Philadelphia.

Franklin would have most likely been witness and participant to this energy and organizing.

War and Family

He answered the call to join the Colored Troops and he served in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, stationed on the USS Princeton. Because of his enlistment record, we know he was five foot four.

Sometime during the early 1860s, he must have married. Because while he was shipping out, a later marriage certificate notes that his first wife died in Liberia.

When he returned from the war he married Anna. They began building a family. Tragically, his daughter Gertrude died of pleurisy (pneumonia) at just two years old. She was prepared for burial by Henriette Duterte, who was also born and raised in the 1838 Black Metropolis, and the first woman undertaker in the United States. Another child, John Edward, died of cholera at 13 months. These weren’t rare tragedies. But they still hurt like only private grief can.

In 1880, Franklin moved to 1125 Lombard Street. If you walk there now, you’ll see that this home was directly across from the building that would become the new Shiloh.

His daughter, also named Anna, was 12. He and wife Anna had just had another baby as well.

Rise of the Shiloh Musical Association

Frank Guinn was thinking about music again.

As musical director, he brought in an orchestra for Shiloh's Easter service of 1883. The deacons weren’t pleased. There was a whole debate over whether horns belonged in church. They agreed—no horns on Easter Sunday. But the wheels were already turning.

In October of 1883, Franklin attended a choral concert at the Academy of Music. Because of segregation, he had to sit high up in the amphitheater.

The Academy of Music looks almost exactly the same today as it did then. Amphitheater seats are all the way at the top.

An idea started to take root.

A full concert, 300 singers strong. With an orchestra. And an organ.

At the Academy of Music.

For Shiloh.

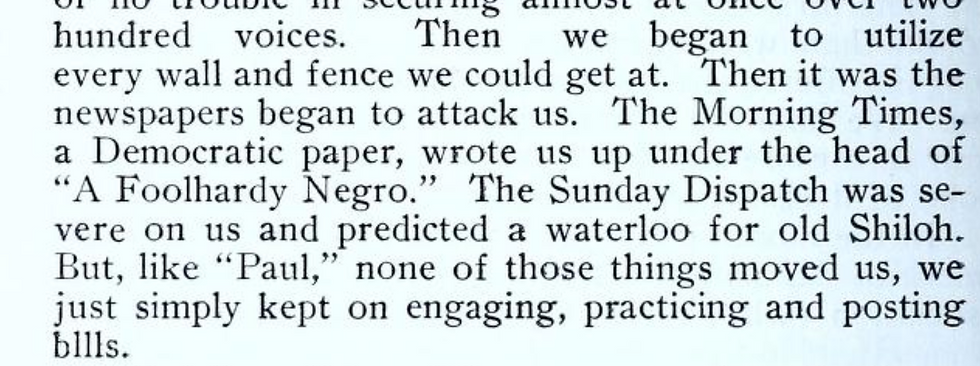

He worked with church leadership to get permission for what many in the church body thought was completely crazy and doomed to failure. Shortly after getting permission, he had singers from all over Philadelphia, and even from Boston, sign up for what was going to be a massive choir.

But then, the next month, Franklin’s wife Anna died in freak accident.

Maybe the plans were already en route and it was too late to stop, or maybe organizing a giant concert was a distraction from grief. Anna's death is not mentioned in The Rise and Progress of Shiloh, which Franklin penned. So we don’t have input into his state of mind at the time.

We do know that he kept on planning for the concert. And the publicity ahead of the concert was not good. He had detractors in the church and also in the press. The white press called him a 'Foolhardy Negro'. But, he says, "we just simply kept on engaging, practicing and posting bills."

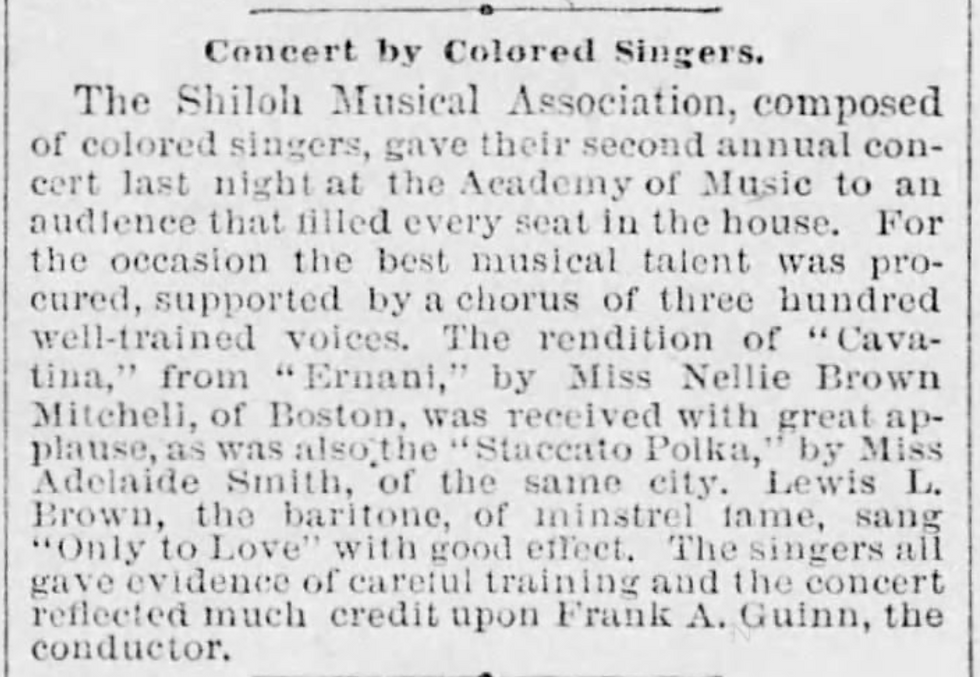

On February 5, 1884, the concert took place at the Academy of Music. This was a huge concert....an 18-piece orchestra, a 300 person choir, and an organ.

And the response was tremendous. A packed house loved the performance. The Philadelphia Times wrote, "The singers all gave evidence of careful training and the concert reflected much credit up Frank A. Guinn, the conductor."

The concert raised $984 (about 30K today) after expenses, enough to help fund Shiloh’s move into a new building across the street from Franklin’s home.

The Shiloh Musical Association also made it’s mark. And it continued to be actively sought after for concerts. John Wanamaker loved the Shiloh Musical Association so much he called them "his choir".

Go Visit The Sites

Both the original Shiloh and the second Shiloh building are still standing. And the congregation is still thriving in a new church building on Christian Street.

The concert at the Academy of Music was historic. Only a decade earlier in 1870 Frederick Douglass wrote a scating letter to The Academy of Music, refusing to speak there until they changed racist policies. While the Academy may have opened its doors to Black people by 1883, Guinn found that he had to go to the top floor - the 'Peanut Gallery' as he called it.

So it was incredible that he decided that Shiloh Musical Association would basically take over The Academy of Music. He wasn't going to do a small concert either ...he was going to do a HUGE concert with 300 singers. One wonders how they all fit on stage!

But I don't think that Franklin Guinn set out to be historic.

He just lived.

A boy fascinated by a junk shop. A scared kid in church. A teenager watching science unfold from a pew. A student of the Black Swan. A man who built a choir that built a church.

Franklin Guinn died in 1912 and is buried in West Oak Lane, under a veterans headstone.

If you visit him, let him know that we remember him and that incredible concert at The Academy of Music.

Questions For Reflection

We've heard of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield's concerts, but not a lot about her musical legacy. How do you think she would react to The Academy of Music concert?

Why do you think Franklin Guinn decided to hold his concert at The Academy of Music?

Franklin Guinn was a classmate of Octavius Catto and Jacob C. White, Jr., both of whom went on to become important Civil Rights leaders. What do you think life was like for these young men during 1840s and 1850s Philadelphia?

Franklin Guinn's book gives us rare insight into the everyday life of a Black church family in Philadelphia. What about this life surprises you?

Sources

1847 Pennsylvania Abolition Society Census Val 3, page 16 https://digitalcollections.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/object/sc267000

Ad in Public Ledger, 11/9/1852. https://www.newspapers.com/article/public-ledger-scientific-presentation-at/152901490/

Find a Grave, Franklin A. Guinn https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/2542278/franklin-a.-guinn

National Cemetery Interment Card. Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962. Interment Control Forms, A1 2110-B. NAID: 5833879. Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. The National Archives at St. Louis, St. Louis, MO.://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2590/records/2095366

Racism in the North https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/racism-north-frederick-douglass-vulgar-and-senseless

Return of Death, City of Philadelphia, for Gertrude Guinn https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-D16S-X96?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AJDK8-H28&action=view&cc=1320976&lang=en

Return of Death, City of Philadealphia, for John Edward Guinn https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-DCBQ-Q3M?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AJDKX-6XM&action=view&cc=1320976&lang=en

State of Pennsylvania Marriage Certificate For Franklin Guinn and Matilda Lanham, 5/26/1887 https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-DZ2S-5ZC?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AQ299-581M&action=view&cc=2466357&lang=en

State of Pennsylvania Certificate of Death for Franlkin A. Guinn, 5/17/1912. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/5164/records/411114?tid=&pid=&queryId=9d516156-8be9-42a6-b537-bd81954cb459&_phsrc=Ovy103&_phstart=successSource

The Philadelphia Times, 11/23/1883. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-philadelphia-times-anna-guinn-frank/168597963/

The Philadelphia Times, 11/6/1884. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-philadelphia-times-franklin-guinn-be/168585547/

US Naval Enlistment Rendezvous, NARA M1953, NARA Roll 22, Film Number 2381763 https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/60368/records/146883?tid=&pid=&queryId=feff502b-cfa1-4204-ade4-79f766b7cb5b&_phsrc=Ovy101&_phstart=successSource