The Two Rebeccas: Building a Black, Feminist, Shaker, and Queer Sisterhood in Philly in 1858

- 1838 Black Metropolis

- Jun 3, 2024

- 5 min read

Imagine that it's 1871 and you've just come from class at the Institute for Colored Youth. As you walk east you see Francis Ellen Watkins Harper but she looks busy as she hurries into her house, so you just smile politely and wave.

And then you hear the sound of women singing. You're curious so instead of walking west as you normally do, you hang a left and walk down Erie street towards the sound of the music.

There is something about the vibration and tone of the voices, as if they are deeply emotional and perhaps moving...no...dancing!

While it's not polite, you really can't help yourself and so you come upon the house at 724 Erie cautiously, trying not look suspicious whilst peeking in the window at the same time.

You see a beautifully appointed room, carpeted, with a large extravagant marble mantel place. The room looks comfortable and warm, and large at the same time.

There are 12 woman moving in a circle in the middle of the room. Their cloths are remarkably plain and don't match the wealth of the home, yet it appears they are most comfortable in this home and you assume it must be theirs. Most of them are Black, one or two are white. They are singing a song.

You watch..mesmerized..as they begin to shake, almost convulsively, as they fall deep into song, and trancelike, dip and fall almost to the floor.

You jump as someone taps you on the shoulder and, embarrassed, you realize you must have been looking for at least ten minutes. Unbeknownst to you, Ms. Harper had followed you down the street and graciously pulled you out of your stupor.

She smiles at you, "That, my dear", she says proudly, "Are the Shakers."

Note: The bulk of this history comes from Jean McMahon Humez' Gifts of Power, a biography and analysis of the writings of Rebecca Jackson. Page numbers noted in the text are from Gifts of Power.

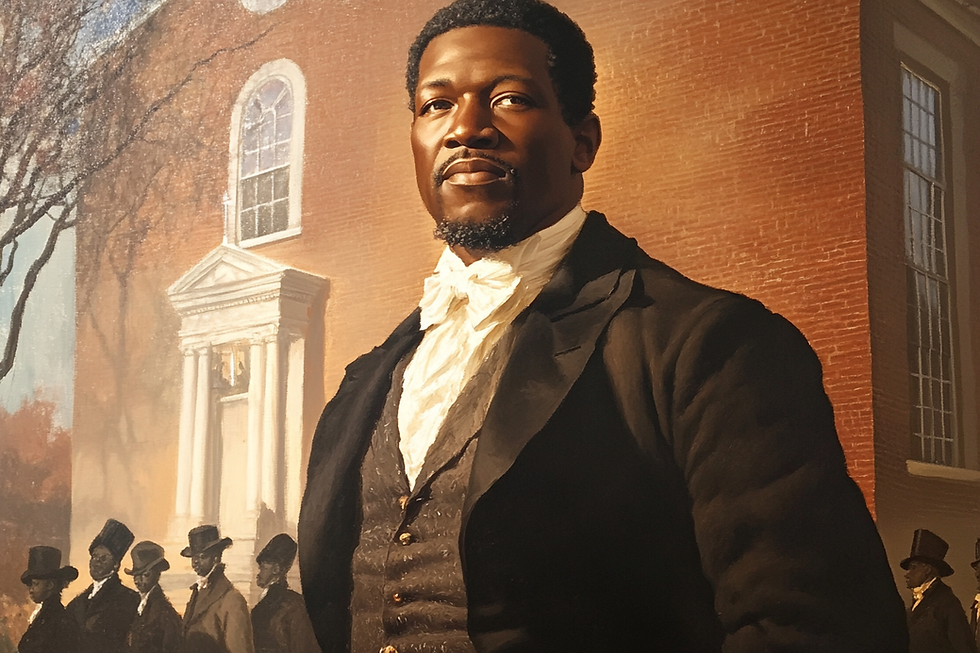

This Pride, we want to celebrate the Two Rebeccas, two Black women who lived together openly as life partners starting in 1837 and bought a new feminist religious ideology into the diverse religious landscape of Black spirituality in the Black Metropolis.

A Spiritual Awakening on Sassafras Alley

Rebecca Cox Jackson was raised in the Black Metropolis. Her brother Joseph Cox was a leader at Mother Bethel AME. She must have grown up hearing Bishop Allen preach on a regular basis. And she and her husband Samuel were living with Joseph on Sassafras Alley in 1830 (1830 City Directory) which was at the corner of 6th and Race and is now under the ramp to the Ben Franklin Bridge.

In 1830, when she was 35, she experienced a spiritual awakening in the middle of a thunderstorm that changed the course of her life forever. In the midst of huge crashes of lightening, she writes that she knelt down in prayer and then...

the cloud bursted, the heavens was clear and the mountains was gone. My spirit was light, my heart was filled with love for God and all mankind, and the lightning which was a moment ago the messenger of death, was now the messenger of peace, joy and consolation. And I rose from my knees, ran down the stairs, opened the door to let the lighting in the house, for it was like sheets of glory to my soul (p. 72).

She started to become aware of spiritual gifts which began as getting clear guidance directly from the divine. At her Mother Bethel women's prayer meetings, attendees would routinely feel the presence of God in their bodies, and respond physically. Jackson writes that she once lied down on the floor in deep spiritual trance for hours (p. 76).

Miraculous occurrences happened to her. She had never been to school, but in 1836 she suddenly gained the gift of reading and writing. In her writings she tells about being able to stop the rain, to converse with angels and the leave her body and fly above the rooftops.

Thank God she wrote because we have very few diaries of the inner life of Black women in the early 19th century in Philadelphia. Notably we have learned so much from Emelie Davis, but her diaries only encompass a 4 year period of her life. Rebecca Jackson's diary starts in 1837 but describes scenes and daily life from 1830 through to 1864. It speaks of all the people around her by name so those looking for their people may want to read this book to see if they appear.

She shared her new found spirituality with her women's groups at Mother Bethel AME and eventually, she began leading her own groups. Her meetings were deeply popular causing Bishop Morris Brown to say "if ever the holy ghost was in any place, it was in that meeting" (p. 21).

She felt that the Bible clearly spoke of sexual abstinence but that her church leaders were not elevating the importance of celibacy. Her growing spiritual gifts and power caused her to want to develop into a spiritual leader. She felt that do so, she would have to leave her husband and her church.

Breaking with The Past and Moving into A New Life with Rebecca Perot

The idea that a spiritual woman raised in the AME Church could leave a marriage to pursue a life of spiritual growth was scandalously radical in 1837.

In 1837, she also met Rebecca Perot. And they became partners, never leaving each other's side. She dreamed one night of a Shaker advising her to move out of her current circumstances. To her that was a signal that it was time to go. And so the Two Rebeccas moved north to live in a Shaker community in New York.

The Shakers were an offshoot of the Quakers and were called Shakers because they shook their bodies in an ecstatic dance as a form of worship. Shaker theology was inherently feminist - where "the Father and the Son of traditional Christianity are balanced and completed by a Mother and Daughter in Deity" (p. 37).

Boldly Challenging Racism in Shakerism and Creating Their Own Sisterhood

Even while Rebecca Cox Jackson developed her devotion to Shakerism, she also felt that white Shakers still bought bias about Black people into the purity of the spiritual realm, which she boldly addressed with them. This confrontation caused some personal fallout in her relationships with white Shakers.

But By 1858 she resolved some of those issues and the two Rebeccas moved back to Philadelphia to teach Shakerism to the Black community.

They lived in 724 Erie Street (now 724 South Warnock Street) with other Shaker sisters in a beautifully appointed house that was "almost palatial" with "fully modern plumbing, central heating" and a large meeting room (p. 40). This location was one block away from the home of Journalist and Feminist leader Francis Ellen Watkins Harper, and around the corner from the Institute for Colored Youth on Bainbridge.

Their small Shaker community of mostly Black women lasted through Rebecca Cox Jackson's death in 1878 and all the way to 1908 when W.E.B DuBois noted two Shaker households in The Philadelphia Negro; nearly 50 years of Black Shakerism in Philadelphia.

When Rebecca Cox Jackson died, Rebecca Perot changed her name to Mother Rebecca Jackson, essentially merging with her life partner.

Concluding Thoughts

The two Rebeccas existed in authentic ways at a much earlier time than any of us imagine a queer relationship could occur openly. We are deeply inspired by Rebecca Cox Jackson's courage to both shake off bonds that she felt were oppressive and to build a new feminist spiritual community with her chosen life partner. This Pride, we honor and celebrate the Two Rebeccas as the queer pioneers that they are.