In 1840 Philly, Westward Keeling Used Classified Newspaper Ads to Protest Racism

- Michiko Quinones

- Oct 8, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Oct 10, 2024

The Rise and Progress of Shiloh Baptist church is the gift that keeps on giving. This is a church history that is told as an autobiography - it could easily be called 'Recollections of Growing Up in Shiloh Baptist'. Many of the early church histories read like the book of Kings from the Bible, but this one...this reads a bit like the gospel of Luke.

From this book we have already gleaned daily life vignettes about Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, who called Shiloh her church home. We have also recognized what must be the third oldest continually owned Black land in the city; the first being Mother Bethel, the second being Campbell AME and then Shiloh. And that's because the church that Shiloh built is still standing and still being used as Waters AME.

I first heard the name Westward Keeling in this book. And I'll be honest with you. I started loving Westward Keeling because...well his name is...

✨Westward Keeling✨

This name just has a ring and a force.

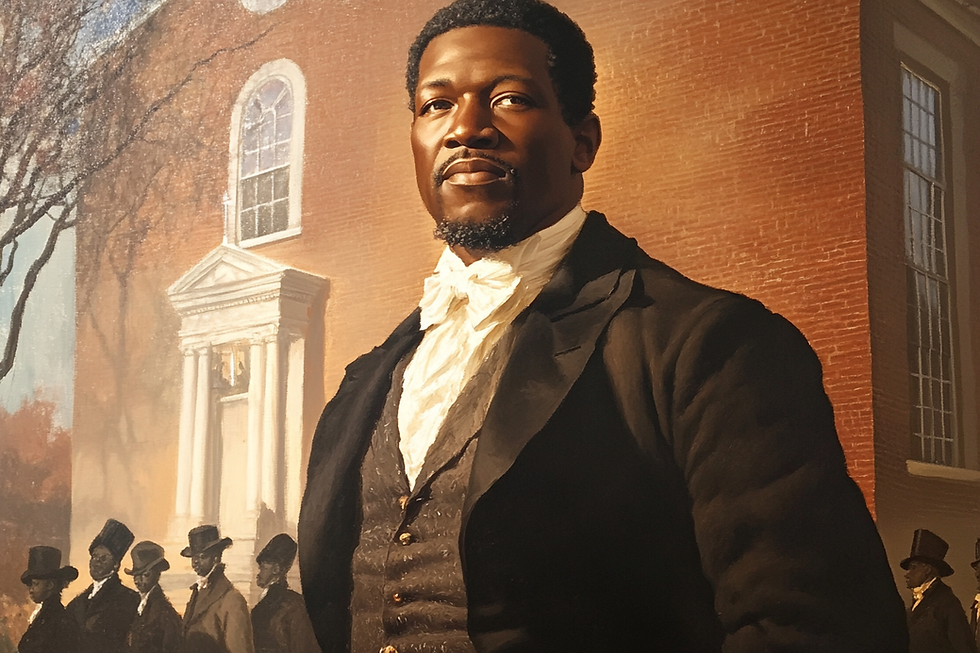

Here is his picture from the Shiloh book.

Ordinary Extraordinary

Morgan introduced the term 'Ordinary Extraordinary' to pinpoint what we love about our ancestors in the 1838 Black Metropolis. Think about living literally 100 miles away from where the nation's legal system would enslave you if you crossed the wrong invisible line, yet you continually are working to set up systems to help people escape that system, even at your own peril.

I mean - that's enough really.

But then, to have been formally enslaved as well? Dealing with that trauma yet still pushing forward to live an ordinary life....to get a job, start a family, join a church...help others. All of that may seem ordinary...but its really extraordinary. Thousands of our ancestors did this, and they are unsung for this valor. So today we're going to sing about about Westward Keeling.

Freeing Himself

Westward Keeling was born in Virginia in 1801. He was enslaved by an episcopal minister named Parson Jacob Keeling. Somehow Westward was able to earn $400 to pay for his freedom. We know that he paid $400 and freed himself from his entry in the 1838 PAS Census.

The 1838 census shows that there were 6 people in his household; 3 were not native and there were 3 children attending school. So we think he must have come to Philadelphia in the 1820s because we know from the 1850 US census that he and wife Rachel welcomed daughter Araminta in 1826 and daughter Emma in 1836.

We know that Parson Keeling was his enslaver from the 1847 PAS census. This was news to me - that sometimes the notes of the 1847 census contain information about the actual plantation or enslaver ancestors freed themselves from.

Taking Action in Philadelphia

If I can think of one word to describe Westward Keeling it would be activist. Because he shows up in so many sources as a community leader, vocally and visibly stating his rights.

First, we see him attending the convention of the Association for the Moral and Mental Improvement (AMMI) of the Colored People Convention. This convention was held in 1838 at Union Baptist Church on Little Pine. It looks like about 100 people attended representing almost all the churches and many beneficial societies.

At this time, the first colored conventions had been held and the temperance movement was starting. This convention appeared to be the AMMI's launch. They must have been very successful and worked hard to encourage people to stop drinking because by 1843 there were thousands of Black people in the temperance organizations in Philadelphia (learn more about that here).

At about the same time, Westward and Rachel opened up a confectionary shop at 4th and Chestnut.

The entrance to the shop, which he specified was the 'basement story' (see below), must have looked like this 1855 photo of Chestnut street.

Here's where we start to hear Westward's activist voice.

Someone refused to do business with him.

In response he took out this ad in the Public Ledger. He advertises fancy shells but also publically takes that person to task, saying that the offender should visit so that he can see that Keeling's store is just "as nice a place as he (the offender) keeps".

We don’t know who the offender was. It could be that Keeling is using the public space of the newspaper to assert economic equality. But if the offense was racially motivated, then this ad moves into the sphere of public protest.

In 1840, a stage coach driver refused to allow Araminta, who was then 14, to ride in the coach. Instead, she had to ride on top of the coach because she was Black.

In what must be one of the earliest public refutations of public transportation racist policies (which were a precursor to trolley car racist policies) Westward takes out an ad asking society in general (represented by the newspaper the Public Ledger) to explain how this could happen, to a child, on a cold November day.

The owner of the stage coach responded in the most uncaring and racially biased way possible.

Our board member Dr. Kirsten Lee, on hearing this story, called out that many of the 19th century public transportation protests were by Black women or concerning the treatment of Black women.

Keeling’s ad is a very early example of that trend, maybe even a first.

Building Shiloh

In the early 1840s, Westward Keeling begins to show up in the history of Shiloh Baptist Church.

He was a Baptist and he attended Union Baptist, but there was something that happened that the church record doesn't want to describe in detail.

There was enough dissension in the 1840 and 1841 to cause a split, and so 43 members of Union Baptist left and went to join First African Baptist.

Most of the 43 lived in the south of the city, in Moyamensing. So a few years later, the leaders of this group met in Blackberry Alley, which is now under Willls Eye Hospital, to form a new church. They became the nucleus of a new church called Shiloh Baptist Church.

Anyone who has grown up in a religious congregation knows that there are some people who are the stalwart consistent presence; those people who are dedicated to the mission and keep the church alive.

It appears that Westward Keeling was one of those people. He quickly became a deacon and played a major role in the church throughout his life, including helping to convince impactful pastor Jeremiah Asher to preach at Shiloh.

By 1845 Shiloh was opening its own church building...which is still standing and still in use today at Waters AME.

Tragedy

By 1847, Rachel and Westward had a few more children, Mary, Andrew, Rebecca and Foksua. They must have had success with their business because they updated their professions in the 1847 PAS Census from 'porter' to 'confectioner' and from 'grocery' to 'cake maker'.

The 1850s turned tragic for the Keelings. In the 1850s census they are a large family. There are two older women living with them, who might be family, or boarders or freedom seeker, or maybe all three.

Sadly, both Mary, age 12, and Andrew, age 10, died in the same year; 1853.

By 1860, Rachel and the younger children are no longer listed in the census with Westward, who is living with Araminta.

And in 1862, Araminta died.

I can't find Rachel and the younger children in later census.

Westward Keeling, however, continued to have a voice. Here he is in 1864, still taking action against racism in public transportation.

I imagine him at this meeting telling everyone that back in 1840 which is 24 years before this, he took out an ad to let everybody know how his little girl has been treated.

Conclusion

Westward Keeling died in 1873 and was buried at Lebanon cemetery, most likely near the bodies of his children. His funeral drew "an immense crowd."

Westward Keeling lived an extraordinary ordinary life. He liberated himself from enslavement, fought for his rights, participated in his community, raised his children, started a business and built a church.

I imagine his did all this as just a matter of living. But it is to these elders, quietly and calmly building stability, that we all owe so much.

🙏🏽Ashe Westward Keeling Ashe!🙏🏽

Sources:

Census

1838 PAS Census

1847 PAS Census

1850 US Census

1860 US Census

Death Records

Andrew Keeling's Death Record

"Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915", , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JK9K-525 : Fri Mar 08 11:21:04 UTC 2024), Entry for Andrew Keeling, 1853.

Mary Keeling's Death Record

"Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915", , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JK9K-PTY : Sun Mar 10 18:47:34 UTC 2024), Entry for Mary Keeling and Westward F. Keeling, 09 Apr 1853.

Araminta Keeling

"Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915", , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:J63P-75D : Sat Mar 09 19:43:50 UTC 2024), Entry for Araminta Keeling and Westward Keeling, 03 Jan 1862.

Westwood Keeling

"Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915", , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JK7M-SXX : Thu Mar 07 13:00:27 UTC 2024), Entry for Westward F. Keeling, 1873.

Newspaper Articles

Philadelphia Tribune Philadelphia Tribune (1912-); Nov 9, 1912, ProQuest page 4

Photographs

Free Library Richards, F. De B. (Frederick De Bourg) - Photographer. (1855). Carpenters' Hall, Chestnut St. at 4th. [Salt Prints]. Retrieved from https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/2591

Books

F. Guinn, The Rise and Progress of Shiloh Baptist